On December 5, 2020, Crime Story published the story Former Prosecutor and Prosecutorial Reform Advocate Accused of Sexual Assault, detailing the allegations against Adam Foss made in a November 20 blog post by Reagan Sealy. You can find that story here.

“We are a business that works with human beings, we know nothing about humans.”: An Interview with Adam Foss

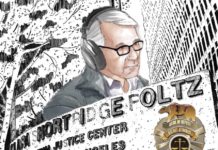

Adam Foss, founder of Prosecutor Impact, is a criminal justice reformer and former prosecutor. In his 2016 Ted Talk, Foss bore witness to the many ways prosecutors squander their outsize power of discretion to deflect vulnerable people away from our overwhelmingly punitive, ineffective, and unfair criminal justice system. His continued work is driven towards transforming the system from within by changing the way its gatekeepers view their responsibility and exercise their authority.

Amanda Knox

Would you mind giving me a brief introduction of yourself?

Adam Foss

My name is Adam Foss. I’m a former prosecutor from Boston, Massachusetts who now runs an organization called Prosecutor Impact, a nonprofit that is looking to give prosecutors the tools and resources that they lack to do a better job in the system.

Amanda Knox

What kind of tools are those?

Adam Foss

So prosecutors, you would think because of the discretion responsibility that we wield, would get some specialized training in law school and we don’t. We get the same 84 credit hours as someone who is going to do someone’s taxes or someone who is going to work in a skyscraper reviewing contracts. We get the same amount of training. And then we are thrust into communities that, for the most part, none of us have ever been in before, and asked to make really hard decisions about people’s lives. And as you can imagine, harm is done not because of the intention of the people going in, but because of the impact of those disconnects between what we are educated to do and what the reality of our jobs are. And so the tools are anything from education, to just an opportunity to look at data and understand long term impact, as well as just experience meeting people who run into the criminal justice system somewhere outside of the courthouse. Lots of things happen, in terms of our biases, when the first time we meet people is inside the four walls of a courthouse. We’re really trying to get people in communities before they start making really, really important decisions that ultimately affect those communities.

Amanda Knox

I noticed that Prosecutor Impact seems geared towards a new generation of prosecutors. Is that because you’re worried that it’s too late to teach old dogs new tricks?

Adam Foss

No, and I really have to update the website. It’s a little two things. One, I went from being a prosecutor to a business owner in a matter of a year, and so probably it was a naive theory of change that the younger ones will be more adept and have more time to engage in our training. That was the idea. I did, again, naively think that people who had been in the job for a little while had been jaded or otherwise incentivized to continue doing what they were doing and so had avoided them at the outset, but have learned a ton since then, and have adapted our models so that we are inclusive of everyone. I’ve met lots of people who’ve been on the job for 25, 30 years who are realizing that something needs to change and they want to use the opportunity that they have and however long they have left on the job to do something positive.

Amanda Knox

What has been the reception to your ideas amongst prosecutors?

Adam Foss

The reception has been good overall. It’s really about the delivery and the approach. I went into this work as a bit of a know-it-all, riding the wave of Ted Talk and really appealing to people’s sense of humanity. I am a black man in the United States of America, I met people who I was prosecuting, I met my victims and in ways that drove the both theory and passion I had around solving these problems. And that’s how I approach people. This is broken, we caused it, and so we should fix it. And as I grew and learned, it became really apparent to me that, despite what we see both on television but also in the courthouse, there’s a disconnect between intent and impact. I saw plenty of prosecutors all over the country who had been conditioned by the system to win at all costs. And I understand that you’ve been conditioned this way because you’re never given the opportunity to do something different. You walked into a courthouse to make decisions about people’s lives through the lens that the law’s equal, the law’s fair, everything is objective, and nothing could be further from the truth. And so really trying to empower prosecutors with a different understanding of the populations that we serve, different tools, connecting them to the community, and change the way that we think about how we do our job.

Amanda Knox

You mentioned your TED Talk, which came out in 2016. And I was wondering if you might talk to me about how you chose to tell your story.

Adam Foss

TED came about sort of through the backdoor. I went from being a line prosecutor and a bartender to being on a TED stage really quickly. I wasn’t particularly well known. Going in, I knew that I had a once in a lifetime opportunity, and I need to use it as best as possible. And so, as opposed to having a slideshow about the criminal justice system and all the way that fails, I thought I would just tell a story. And I had lots of stories to choose from. But I chose one that I thought that people could empathize with. I chose not to tell a story about something that happened around a violent crime. I chose a theft crime because I thought that people would be able to sympathize, and it’s been quite the journey since then.

Amanda Knox

I’ve been thinking a lot about the distinctions between nonviolent and violent crime, nonviolent and violent offenders, particularly in thinking about how recent criminal justice reform has been geared towards providing opportunities to solely nonviolent offenders. Why do we have such resistance to people who have been accused of violent crimes?

Adam Foss

From the time that we are babies, we do not discuss violence in any way except the moral failing of an individual person. We don’t understand violence in any other way except a character flaw of an individual and we never have allowed ourselves the opportunity to talk about violence [as] the manifestation of something that is usually health related. It requires an amount of empathy that we have not allowed ourselves to have for violence. And the media has done a really, really good job of creating narratives around violence that have made reforms nearly impossible. Because when we do something that looks like reform and something violent happens, we look at that at the expense of all the other good things that happened because we’ve taken that risk. And we shut things down. And it is frustrating for many reasons. One, we know is that people who commit violence recidivate at a really, really low rate, particularly because most of the people who commit violence are young and impulsive, and it’s something that we grow out of. Number two, our acculturation in this country around violence breaks down along racial lines, and so you get these really severe racial disparities in how we deal with violence in this country. And three, our response to people who have committed violence is to meet them with more violence, and we create bigger problems.

Amanda Knox

How have you seen the political and social landscape change between 2016 and today?

Adam Foss

There’s certainly a lot more attention around the issues. I am reluctant to say that there has been a shift that will not retreat as soon as something bad happens or as soon as something else comes up in the media. For a moment there was a spotlight focus on prisons. All of a sudden you had all these people talking about releasing people from prison because of coronavirus, and there was a moment that people for the first time had really acknowledged how barbaric the system is, because we were making the decision to keep people locked up to die. In that moment, I was optimistic that we could at least push enough people out that we can build infrastructure to not let them come back in. But we started talking again about who should come out and even the reform community was doing this thing where we were walking backwards in our language, and then George Floyd was murdered, and all of a sudden the conversation around people who are dying in prison was gone. We were focused on another tragedy, and in the meantime, the coronavirus was spreading through the prisons and killing people. The media is fickle, as is the attention span of people, particularly those people who do not have contact with the criminal justice system, who believe that emptying prisons and emptying jails means putting putting “the good people” in danger, sending the message to the community that they can run wild and nothing will happen to them. All of these narratives that we’ve told ourselves that are absolutely false. So I’m cautiously optimistic.

Amanda Knox

It seems that the focus of the protest movement is reallocating financial investment in law enforcement and putting that towards education or intervention treatment in disadvantaged communities. What’s your take on that vision, and how realistic it is, and if it’s the right focus?

Adam Foss

The reason that I’ve focused my attention and life on prosecutors is because that is really the gate to the rest of the justice system. The opportunity to go even further upstream and talk about what if we did something other than arrest people? What if we did something other than shoot people in the back or lean on their necks? What an amazing world that could be. So the vision, I think, is a beautiful one. And I’ll use this example. When I hear “defund the police,” Boston has a police force that I worked side by side with, full of amazing police officers with a smattering of terrible ones, and a legacy with their community that is not great. I will give credit to the Boston Police Department. There has not been an officer-related shooting and certainly not an officer-related death in many years, but still, the things that happen between the headlines have caused this division in the community. And so 55,000 people come out and march and ultimately what they’re saying is, “Please, you’re hurting us.” And I thought for a moment with the leadership that we have in the city, that this might change things. And then the next day I see the Commissioner of the Boston Police Department, who is an African American man, standing next to the US Attorney for the district of Massachusetts, celebrating a “gang takedown” in the neighborhood that I used to live in. The old ’90s, chest pumping, “we got ’em” presentation of their indictment. They arrested 31 young men. They recovered some amount of cash and 20 handguns. They stood there in front of cameras and talked about the length and duration and quality of this investigation. The FBI, the ATF, the Boston Police Department, the Mass state police, 11 other policing agencies from around three states, numerous search warrants, all of this surveillance. And on the back end of that we got 31 guys off the street and 20 guns, and to someone who’s sitting at home watching the television, that probably looks like a major accomplishment. And I don’t want to minimize the work that the officers were doing. But for all of that bluster, for all of that money, what we got off the street were 31 young people who we’ve known for the last 15 to 20 years. Three of the young people who were arrested, I knew them from my time in the DHS office, and one of them stuck out to me because I remember when I met him, he told me when he was 11 years old he was shot in the face. And when he was shot in the face, 11 years old, he said he went to this hospital for a little bit, got checked out, but then immediately went to a police station, was interrogated, and that informed his relationship with the police. And this young person has been telling us, “I’m a hurt person. I’m damaged. This is traumatic to me.” And instead of investing all of this money that the US Attorney was airing out to the press, we could have invested that in this young person when he was little and maybe avoided all of the trouble he ended up getting himself into. And so the vision of a future where we’re reinvesting police money is achieving what we want, which is safety, but doing so without waiting for someone to get themselves into a federal dragnet.

Amanda Knox

Do you think that any of them are feeling conflicted right now in the context of everything that’s happening today?

Adam Foss

It’s really a continuum. And I will give that to them that what they’ve accomplished may prevent further harm from these young people. But we’ve now got them after they’ve allegedly committed three other homicides. And all that that that they’ve accomplished is what we accomplished in the 1990s, which is you’ve created a vacuum in a community that is going to be filled with other young people who still have access to handguns, still have these gang conflicts, see a bunch of their mentors and heroes and brothers and relatives going into a system that they view to be unfair. We spent a ton of money doing so and the young people who are now filling that vacuum in the community still lack the resources that the 31 young people that were locked up never had.

Amanda Knox

Should we just blanket give forgiveness for violent acts of crime to establish a world where everyone’s sort of now on an equal playing field, and it’s not just this retribution for retribution for retribution? I’m trying to imagine how this transition period, where we stop having a law enforcement structure that is so retributive, how do we do that transition or make that transition while acknowledging that violent crimes have been committed and harms have been done?

Adam Foss

Can you ask me a tougher question, please? Now, you use one of my favorite words, which is accountability, something that we throw around a lot in the law enforcement world all the time. And I think one one thing that should be called out, one thing that is driving the distrust on the law enforcement side, we love talking about holding people accountable, but do not model behavior at all. I am of the mind that we have to try anything that will get us out of this mess because this is not working. We never had a good response to violence, and yet we told ourselves that this was the best way. It’s a really hard leap for people both on the law enforcement side, but also in the general public, because we’ve never seen what it looks like to deal with violence with anything other than a strong show of force from police, incarceration, and then this labeling of you being an offender. Having had my face in violence over the last 15 years, and understanding from a granular level what drives gang violence, particularly with young people, is exactly what you’re talking about, which is this cycle of retribution. And that is never going to end unless we have something that looks like a ceasefire with professionals that are not law enforcement, who are counter radicalization professionals. We will not get there unless we make that kind of investment. Because what is the saddest thing to me about young people who are shooting and killing each other is they are more similar in all of the ways that make them actually really vulnerable to the criminal justice system, and they are fulfilling their own prophecy by continuing to drive violence and a lot of it is just abject fear. Rarely are these are young people these incorrigible cold blooded killers that people make them out to be.The moment that you meet them, you’re like, “Oh, you’re a little kid. You have all sorts of problems with trauma, you have all all problems with masculinity, you have all sorts of problems with fear.” And when you look at it that way, it becomes really, really clinical. And if we could just release ourselves of this ego around violence, and if instead approached it as a health issue, we might actually make headway.

Amanda Knox

Why is it that we are so afraid of young men? And why is it that young men are so afraid of each other and what do we do about that?

Adam Foss

We are afraid of young men because we have again just been socialized to be afraid of them, particularly young black men. How we see them in the media, how we talk about them, how we portray them as these impulsive, out of control, idiot, troglodytes that are just out for a good time. I mean, listen, our brains are chemicals. All those things create an impulsivity, a lack of connection with future consequences. If we understood those things about young men, we might have a different approach to young men, but we don’t. We also just do a really terrible job of raising young men. You steer into conversations around masculinity, around conflict resolution, around what happens when we are victimized, which is something that we have actually socialized our boys not to do.

Amanda Knox

Do you see the narrative around boys changing?

Adam Foss

Toxic masculinity is a buzz phrase that we’ve kicked around for a couple years. I think there certainly is the environment to have a broader conversation. But it’s deep work that has to be done. And it’s deconditioning work. We can’t have a conversation about toxic masculinity and call it a day. You can’t undo what has been done so pervasively for generations by shooting a documentary about it, or having an hour long training about it. It is committed and deep work that we have to do for adults in the way that you would work on a Rosetta Stone to learn a new language.

Amanda Knox

Speaking of toxic masculinity, I’m curious to know if you think that discussions of it have been productive or counterproductive overall, because I think it largely depends upon how people are talking about it. Some people think there’s something inherently toxic about being masculine, and other people say, “There are expressions of masculinity that are toxic, and there are expressions of masculinity that are not toxic.” Do you think that there is a sort of disconnect between productive and counterproductive ways of thinking about that? And is there a parallel with racism?

Adam Foss

Yes. Now more than ever, I’ve seen people being thrust into conversations around racism in ways that I never have. And as a result, a bunch of people are being asked to facilitate those conversations without a great roadmap. You have some people who talk about racism as if it is the moral failing of an individual. There are people who are racist and who are not racist. And that creates a whole bunch of dynamics that I think can make the conversation really counterproductive. People run for the exits, people feel hurt and unheard, they feel judged and don’t want to participate, and you don’t really get anywhere. Whereas a more restorative conversation around racism and around masculinity frames it as a social determinant. It happened in the same way that we learned how to speak a language, that we learn how to ride a bike. It happens without us even knowing it, and then it stays in there. And without deep work, which is uncomfortable and inconvenient for a lot of people, it’s going to prevail. We have a branding problem with everything. We want to make everything pithy, and so the term toxic masculinity came about, and you see people who clearly are still struggling with their own masculinity issues rejecting that phrase and there’s nothing productive happening. You really have to show radical empathy that will allow people to ask questions and explore masculinity so you get learning as opposed to feelings of hurt and judgment and disagreement.

Amanda Knox

What’s on your mind these days?

Adam Foss

What’s happening with police and in our communities, and recognizing that people aren’t really in the mood to have a conversation with police, that people have lost their patience. I think we need to even take a moment and have more empathetic conversations with police, with people who we view to be racist, with corporations who at this very moment are freaking out about racism not because they’ve suddenly realized how harming it is to their staff, but because they’re going to lose customers. While that is super frustrating, again, taking that beat to have a restorative conversation around resolving the problem is something that I’m doing right now. And I always come back to what we’re losing out on in terms of the people who are going into our criminal justice system and we’re losing them. People who are being harmed in the communities. We have a tendency in the criminal justice reform space to forget to talk about survivors. There are lots of people who are silently suffering, because their Hobson’s choice is, “Do I pick up the telephone and dial these three numbers which invites the real threat that the police come to my house, that something bad might happen, or do I just endure whatever harm is happening in my home?” Whether it’s domestic violence or sexual abuse or gang violence, that, to me, is why we really need to reform the system. Because we know that harm begets harm. We know that if we’re not serving victims of crime, then they’re at an increased likelihood to be victimized again and or perpetrate violence of their own. And we can sit back and wait for that to happen and then blame them and shame them and punish them for their failure, but the creation of that Hobson’s choice does not exist in communities where the police are viewed as friends. The sad narrative that we don’t often talk about are those people who were suffering in silence because they don’t fit the mold of the tenacious, brave, resilient survivor that has the privilege to pick up the phone, can go through 17 court dates, missing work or childcare or healthcare while their case processes through the system, and are standing there at the end of the day to give a victim impact statement. That is a fraction of the victims that are in our communities. And until we steer into that reality, then our continued banner that we fly under, that we are serving victims, has an asterisk next to it for me.

Amanda Knox

That raises the question, what is the criminal justice system for? Who is it ultimately serving? Is the whole thing broken, or does it need to be reformed?

Adam Foss

Here’s the deal: our criminal justice system was invented centuries ago. The people who were inventing the criminal justice system were doing so with the set of information and tools that they had at the time. Not only did they believe that this was going to be the way that we were going to solve problems, but they also believed the world was flat and that there were witches. These erudite, academic white men in wigs had an undue amount of influence over the way that things were set up. And that is how we created education. It’s how we created medicine. It’s how we created the criminal justice system. And while medicine and education have radically changed, the criminal justice system has existed almost untouched since then. We’ve added a few things here, we’ve taken away a few things there, but ultimately, the way that the criminal justice system was set up and the beliefs behind why you needed it is ultimately what we think now. It’s not a question of, “Is it broken or not?” It’s “We never did the thing that other institutions have done.” Which is research, test, fund, train. We’ve missed out on all the other things that have improved other systems because we have this arrogance around the tradition of the criminal justice system, and if you were asking a group of scientists and psychologists and engineers and designers, they would tell you like, this is ridiculous. And not just that, young people would tell me all the time, “Do you think that my life is so privileged that I have the opportunity to think about what might happen to me if I get caught with a gun in the streets? I live in a very different reality than you did when you were 17. While the threat of the criminal justice system to you might have been scary because you had a nice house and your parents would have been mad at you, and you might have gotten your car taken away, and you might have hurt your scholarships to college, I don’t live in that environment.” We are a customer service business who disregards its customers. We are a business that works with human beings, we know nothing about humans. We are a cause and effect system that has never really spent a lot of time looking at the cause, and blames individuals on the effect. And the reason that we do not freak out and spend all of our time trying to solve the problem is because for 99% of us, it never crossed our doorstep. It is something that we watch happening on TV, and we celebrate it because Dick Wolf has created an entire empire that tells people, “This is working, and the bad people are away from you because of that.”

Amanda Knox

What do we do? And who does it?

Adam Foss

Well, that is the optimistic part of this. We’ve literally never done anything. We have tried to reform the system by policy decisions, and the issue with policy is that they’re words on a page that do very little to affect the culture. The Delta for opportunity is wide. Minor input can yield tremendous output. Our prisons are operating at a 70% failure rate. If we get that to like 50%, we’re saving millions of dollars and probably everybody’s winning a Nobel Peace Prize. And it’s a funny thing to think that if we go from terribly shitty to moderately shitty, that’s something to celebrate, but that should be optimistic. What it is going to require is people who are running the system to divorce themselves from the waxing and waning opinions of the mob, and just understand that we are the people who have to do things that the public might not like. It’s not because the public is terribly informed about what’s happening; the media has a tremendous role to play in leaving this legacy of sensationalistic storytelling around crime and punishment. It is going to take all of the economists to realize that the private sector is losing out on a ton of capital from the criminal justice system because a humongous segment of our population cannot participate in the economy. We are creating classes of people that cannot contribute.

And it’s going to take the institutions to allow feedback. The criminal justice system is a terribly fraternal, hierarchical system that values the intel of the people who sit at the top. It’s like a hazing. We don’t really care what you think until you are a senior police officer or senior prosecutor or senior judge. It’s like an egotistical, traditional legacy mindset. Let’s give everyone the opportunity to create, to ideate, to interact with leadership, to be part of the community, to try ideas, and to fail. And the last part is we have to stop looking at failure as a big thing. Because when we do so, it arrests us from trying different things. And the analogy that I use all the time is the airline industry. Obviously when they invented it, there was a lot of failure, and the failure was catastrophic. They could have looked at those failures as a reason not to put airplanes in the sky. But they didn’t. They looked at failure as a positive learning experience, learned from those mistakes, and built improvements to the system that ultimately allows for us to put millions of planes in the sky every single year with very, very low failure yield. And so from the criminal justice system, when you think about all the things that prevent us from trying new things, the ultimate fear is something bad is going to happen. We need to inoculate ourselves to the idea that we can control for everything bad. Things are going to happen. The question we should be asking ourselves is, when is a severely high violent crime rate, when is pervasive domestic violence, when is the unaddressed sexual abuse of children and women and LGBTQ youth, homeless people, when are those failures going to outweigh the risk that something bad might happen if we try something different?

Amanda Knox

Do storytellers have to abandon the concept of villains in order to tell a new story?

Adam Foss

No. What I am suggesting is when we are creating villains, we should figure out ways to have a deeper understanding of why people are villains. At the end of the day, we are primates who just got an improvement on our brain. We are a very juvenile species and that creates a tremendous amount of imperfection in everyone. It manifests in different ways depending on the environment that you’re brought up. And we have these concepts of nature versus nurture, when it’s actually just a mash up of the both. You can tell really good stories that don’t need to make the villain some completely dysfunctional pathological demon. We can still make them a human being so that we can go about the business of creating empathy in places that we don’t have it. We can break down these barriers and stop using words like, “This person deserves the rest of their life in prison.” We wouldn’t talk like that if we had empathy for everyone, including the people who are doing the really the most heinous stuff. There are some people who need to be separated from their communities. Why does that separation have to occur at a draconian place where everything is about shame and blame and torture? Why can’t it be in a place that is isolated from the community, which is punishment in and of itself, but also is filled with people who are trying to resolve the things that are making this person manifest the scary things that we don’t like about them? I don’t think that that is too much to ask.

You can follow Adam Foss on Twitter and Instagram: @adamjohnfoss