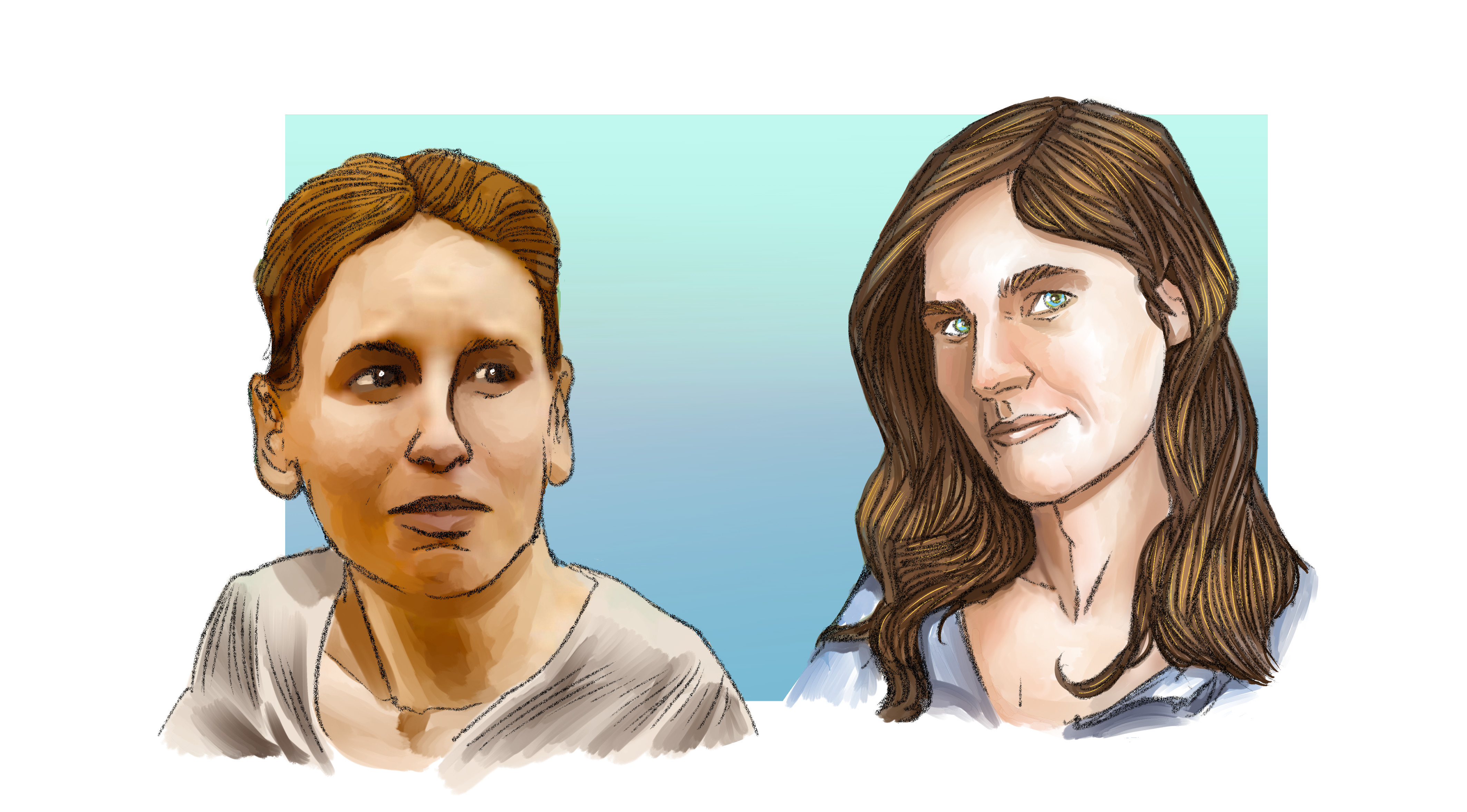

An Interview with Heidi Goodwin

In 2003, a jury convicted 24-year-old Heidi Fero of first-degree assault in connection to a 2002 incident that inflicted permanent brain damage on 15-month-old Brynn Ackley. Physicians diagnosed Ackley with the now discredited shaken-baby syndrome, and Fero was sentenced to 15 years imprisonment, later reduced to 10 on appeal. Fero served her full sentence, but in 2016, her conviction was vacated when pediatric trauma experts debunked the faux science originally used to convict her.

Heidi Fero, now Heidi Goodwin, serves on the advisory board of Healing Justice, an organization dedicated to bringing together victims of crime and victims of wrongful conviction, and addressing the individual and collective harm caused by wrongful convictions.

Amanda Knox

How are you holding up?

Heidi Goodwin

I mean, there’s a lot of uncertainty, which is unnerving. I remember being inside and we would get locked down and that feeling of uncertainty of, “What was gonna happen? Are we going to get out of here today? Are we going to get to our programming? Or are we going to lose programming?” That feeling of no control of what’s happening in the larger scheme of things. We have five acres. I can control what’s happening here.

Amanda Knox

Do you mind doing a short little description of how you came to be a part of our club of people who have suffered from the criminal justice system?

Heidi Goodwin

Sure. My case actually started back in 2002. I went to trial in 2003, however, I didn’t actually start serving any time until 2006, because I was out on an appeal bond for three years. So I was wrongfully convicted of the misdiagnosis of the shaken baby syndrome and started serving time in 2006. The Washington Innocence Project took my case in 2007. I, unfortunately, ended up serving all of my time before we were able to finally get relief from the courts. I was released in 2014. I did a total of eight and a half years. And then in January of 2016, the Washington State Appellate Court unanimously overturned the conviction based on new evidence.

Amanda Knox

How have you translated that experience into what you do today?

Heidi Goodwin

To answer that question effectively, I kind of have to go back to even before the trauma started. I had a really outrageous and unusual childhood. I was born in Portland, Oregon, but I spent many of my years on the coast. My dad raised me on a dairy farm. There was a large logging community there. My mom was also a hippie. And she ran with people at the time who were well known to the community, like Jerry Garcia, Ken Kesey, these were all figures in my childhood. My mom was an activist. She was one of the ones that went to stop the white train when Reagan was in presidency. Once I got old enough to do my own thing, I felt like I needed to get away from that. I wanted a safe, and secure, and stable, white-picket-fence type of life. When I then got convicted of something that I didn’t do, that childhood experience actually lent to my ability to function within this trauma and this environment for eight and a half years. It allowed me to pull out from those roots all of these things that had been inactive in me. In a way it was discovering who I really was, and embracing that. Just having a voice, being educated, understanding the universe around me and how it works and not being blinded behind that white picket fence. Not ignoring that there are bigger things than just us in this world. Once I was inside, and I was around other women who were also seeking truth and education and growth, it started to stir those same things up in me. I got to be a part of some pretty amazing programs. We founded a program called the Women’s Village. We had full backing and full support from administrative staff, and it was basically just a program of us utilizing the skills that we had to provide for ourselves in a various degree of ways, whether it be family unification or conflict resolution or GED. Because, as we all know, programs get cut due to budget. But what we realized is that we had it within ourselves to teach each other and support each other. And so now that I’m home, I found that solid identity of who I was inside. I’m back to being that person who believes in advocating and having a voice for others. Early on I realized that those of us who have been through this experience, we’ve had a lack of assistance and support once we get home, and the people that are going to fill that the best are us. My focus is, “How do we build this network for those who are coming home amongst ourselves?”

Amanda Knox

Is there anything else that incarceration inadvertently helped prepare you for the current challenges that you’re facing with the pandemic?

Heidi Goodwin

The uncertainty is definitely hard to deal with and I have a deep, deep, deep distrust of the deep state. I have to battle with myself of not going too far down the rabbit hole of, “Are they lying to us? Are they even telling the truth? What’s really going on?” One negative that has triggered me was the plexiglas up in the stores. It kind of reminded me of inside, when you have to visit through glass. For a minute that threw me. But overall, it’s so strange because, since I’ve been home, it’ll be six years this July, I don’t feel organized completely. I still get overwhelmed in the grocery stores. I still kind of feel like I can’t keep up with community out here, because of the ingrained way that we did things inside. I feel like I fumble it a lot. However, since this pandemic and the social distancing rules have been applied, I have found a focus within me, because it almost feels familiar. And I feel more organized, more focused, and more grounded than I have in the last six years of being home. It’s like, “I know how to do this.” And I don’t know if that’s a good thing. But it’s like, “I know how to do this. I know how to wait things out.” That makes sense to me. When we’re inside, we don’t have many choices. And since I came home, I have had to leave the grocery store crying because, like, a wall goes up. And even if I have a list and it’s all written down in front of me, everything will become blurry, and I can’t manage the chore, and it’s very frustrating. But since this started, I have not had that issue. I’ve gone into that store and I’m like, “Okay, this, this, this to get us through the next two weeks or 30 days, and good to go,” and my freezers full, my pantry is on. And I haven’t been able to do that the entire time I’ve been home, but now I can.

Amanda Knox

It’s almost like this quarantine has triggered your mission survival prison mode. Do you find yourself uniquely equipped amongst the people around you to take on this challenge?

Heidi Goodwin

You know, that’s a really good question. We’re a multi-generational home here. My grandparents moved in with us about three years ago. They’re 97 and 89. We have my little daughter Havana, who is two years old. And then it’s Juan and I. And then prior to her mother being released, I had been raising a little girl named Stormy. She’s 16 now, but we’ve had her since she was 12. Her mother was inside with me, and both of our daughters participated in the Girl Scouts Beyond Bars program. When I came home, within a few years, her mother had asked me if I could help with her, and we had her for about two years before her mother came home. Now her mother came home and she’s been living with us for the last year. She helps with my grandparents, and we’re kind of co-parenting this little girl. So we have a full house. And then my older daughter comes and goes also. She’s 23. I’ve, kind of, gone into this management mode. When this first started, right away, like, my grandparents, we have to shut everything down. I’ve had so many ups and downs with them over the last couple of years, I just did not want them being exposed to anything. I wasn’t really concerned about the rest of us initially, but my older daughter went through an accident a few weekends ago. But at the hospital, I wasn’t allowed. They let me see her for a few minutes, and then I was not allowed to stay with her. I had to go through all these checkpoints, and everybody had all these gloves and masks and shields on. And, I think for the first time, that was when it hit me, this isn’t just my grandparents. Juan and I are both immune compromised. We’ve both had cancer. If one of us were to become ill, how would the rest of this home function without one of us? So I took a step back and was like, “We can’t afford any one of us, like, one of the legs going out from this table.” I think that that’s what has played into focusing me. I know how to do this. I know how to get through something.

Amanda Knox

How does this feel different than going to the grocery store and being overwhelmed? Why is this more like prison than the grocery store?

Heidi Goodwin

I think prior, when I would go to the grocery store, the vast choices sometimes overwhelmed me, plus the crowds of people. The difference now is when I go in, I’m not seeing everything. I’m not seeing other people. I’m getting what I need and getting out as quick as possible.

Amanda Knox

In prison, the challenge is the limitations, right? There’s social isolation, there’s feeling like your life is no longer in your own hands. And these are the kinds of challenges that suddenly everyone is finding themselves immersed in. And I feel like a lot of us formerly incarcerated folks are like, “Oh, yeah, been here, done that.”

Heidi Goodwin

Exactly. I’ve seen a few that can’t stand it. But I feel like the majority of us are like, “We got this.”

Amanda Knox

I know that you’re helping a lot of formerly incarcerated people reintegrate into society. Can you talk to me about that?

Heidi Goodwin

I serve on the advisory board for Healing Justice. I also have, let me find my little list here, because I check in with them regularly. So I have, between Washington and Oregon, about 14,15 exonerees that I stay in contact with on a regular basis. We’ve been having actual Zoom meetings face-to-face, some of them have attended Healing Justice retreats. I just kind of try to keep everybody tucked in as much as possible. When I initially was brought into the community, I kept hearing this conversation about how we need this help, how we need this help. And a lot of it revolved around money. “Oh, well, we need money to do it, we need money to do it.” And I’m thinking, “No, we don’t. We just need each other.” We don’t need money to do just a simple phone call to each other or a Zoom meeting. That’s been more of my approach, working in the background, despite not having funding to do it or being an official organization. Now, I fully believe and push and support Healing Justice. I feel like they are the next level of what is happening with aftercare for exonerees, and not just exonerees, but anyone that’s been impacted by a wrongful conviction.

Amanda Knox

Would you mind describing what Healing Justice is?

Heidi Goodwin

So Healing Justice was kind of born out of two women, Jennifer Thompson and Katie Monroe. Jennifer Thompson is a survivor of a crime. She was raped and held at knifepoint and had to escape. She inadvertently identified the wrong man. His name was Ronald Cotton, and he spent 11 years in prison before DNA determined that he wasn’t the person. After all this was exposed and Jennifer had some time to process it, her and Ronald became very close. They wrote a book together named Picking Cotton, basically describing what had happened and putting back the blame on where it ultimately lies, which is the person who actually committed the crime and the justice system that had failed everyone. That’s how she was brought into our Innocence Network and community. Katie Monroe, her mother Beverly Monroe, was convicted and incarcerated for a crime she did not commit. And so, at some point in the last several years, Katie and Jennifer became acquainted and started having this conversation about the fact that there is more than one harm. So it’s not just the exonerees that’s harmed, and it’s not just the exonerees’ family that’s harmed, but it’s also the original survivors. Everyone’s impacted by this wrongful conviction. These circles are concentric. And the best way to work through healing is to combine these concentric circles in a restorative justice setting, to allow people to work together through this healing, because it’s ultimately the same system that created the harm. It’s no one else, not in the criminal justice system, or any other peanut gallery out there, dictating on how this person should move on and heal. Healing Justice puts all of the key people back into the center of the process. Back in control. This really strong organization is the most comprehensive in addressing the harm that was done to everyone by the criminal justice system.

Amanda Knox

There are multiple victims.

Heidi Goodwin

Right. All harmed. “All harmed” is the hashtag that we use. And for whatever reason, it just is more solid than anything else that’s being done. I remember the first retreat that I went to, my breath was literally taken away by listening to a crime victim. As I listened to what she went through, believing all those years that this was the person that hurt her, and then understanding and processing that, no, this was not the person that hurt her. And then the guilt that she carried because she had helped to incarcerate the wrong person, and then trying to move past that. That guilt really shouldn’t be hers to carry. The reach of the criminal justice system and the damage that they’re doing is so much larger scale than what we realize.

Amanda Knox

Do you have any further thoughts on surviving the pandemic or on the plight of the either currently or formerly incarcerated at this time?

Heidi Goodwin

There was one thing you said about, “Thank goodness that we’re not inside right now,” and I could not have agreed with you more because I actually was diagnosed with stage two breast cancer the last year that I was inside. I had to have a double mastectomy and go through 12 weeks of chemo and six weeks of radiation and was hospitalized. I got pneumonia, my immune system was so shot. And it was terrifying being inside and going through that, because, as we all know, medical care is so shoddy in there. We had to fight tooth and nail to get everything that I needed. And there was another woman who was diagnosed with the same thing at the same time that I was. She did not survive. She passed away after I was released. All I can say is she didn’t have the same support. She didn’t have the same people advocating on the outside. And so I’m so scared for the people inside right now.