The COVID-19 pandemic and its widespread disruptions have caught the Los Angeles County Superior Court system completely flat-footed. Even in the best of times, there are gaps in what we can only call the ergonomics of the court system, with the Airport Courthouse standing as a shining example of contemporary design and infrastructure, as opposed to downtown’s moldering Foltz Criminal Justice Center, which looks and feels like something out of Dragnet. (And in both instances, entrance security protocols and equipment are appropriate to a small, regional airport, not big-city justice facilities.) But these are not the best of times. As Kary Antholis reports in COVID-19 Chaos in L.A. Criminal Courts and Jails, the LA courts in the Age of COVID-19 witness daily scenes of chaos and uncertainty.

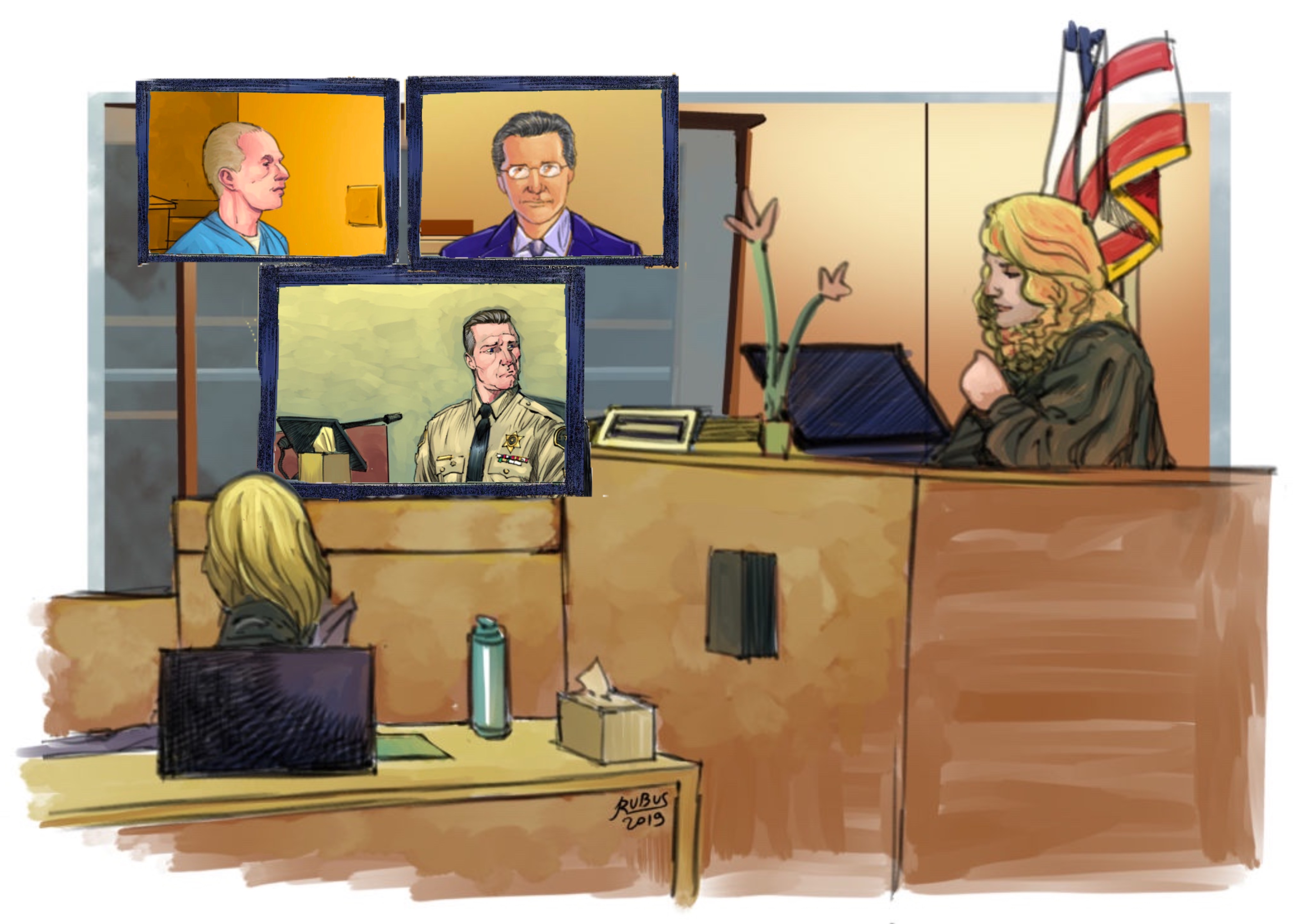

The novel coronavirus has exposed one of the LA court system’s most fundamental flaws — its spotty technological capabilities. Los Angeles, a city that is widely considered the media capital of the world, boasts courthouse video- and tele-conferencing systems that belong to the age of Hazel and not Quibi. To date, remote access technology has been a regular feature in Delinquency and Mental Health hearings, with defendants often facing video cameras in detention facilities far from county courtrooms. Some civil proceedings are conducted via Court Call, which utilizes speaker phones but also has webcam capacity. But these innovations have yet to reach the criminal courts… and now those courts are scrambling. The Court’s Media Relations department revealed that Department 40 at the Foltz Criminal Justice Center is piloting remote appearance technology, while the busy Department 30 is currently piloting video arraignments. (A criminal courtroom in the Pomona South Courthouse has also been piloting remote technology, but with all criminal trials suspended, that experiment is on hold.) And as of this writing, the Van Nuys Courthouse is also experimenting with video arraignments, open only to courtroom staff and their “justice partners.” This innovative spirit is admirable and absolutely necessary. But when Orange County courthouses are being closed in order to retrofit them with remote access equipment, LA’s “piloting” initiatives still feel too little and too late. As the LA criminal courts struggle relative to other jurisdictions to administer available technological tools in order to confront the current public health emergency, it’s important to trace how this “technology gap” was exposed in the first place.

On March 23, 2020, the Honorable Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye, Chief Justice of California and Chair of the Judicial Council, issued a statewide emergency order “requiring superior courts to suspend jury trials for 60 days, unless they were able [to] conduct such a trial at an earlier date, upon a finding of good cause shown or through the use of remote technology; extending statutory deadlines for holding last day trials in criminal and civil proceedings; and authorizing courts to adopt any proposed local rules or rule amendment intended to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to take effect immediately, without advance circulation for public comment.”

One week later, on March 30, 2020, Cantil-Sakauye expanded on this order, authorizing superior courts to significantly extend the time periods allowed for arraignment, preliminary examination and time to trial. Parallel with these unprecedented amendments to the California penal code, the Chief Justice “found good cause… to support courts in making use of available technology, when possible, to conduct judicial proceedings and court operations remotely, in order to protect the health and safety of the public, court personnel, judicial officers, litigants, and witnesses.”

The Chief Justice’s emergency orders present the state’s superior courts with several fundamental challenges. Most prominent are the troubling due process implications of the suspension of jury trials and extension of timelines for essential judicial proceedings. Equally problematic, however, is the orders’ implied faith in the capabilities of currently available technology. As we shelter in place and work from home, many of us are Zooming and FaceTiming, only vaguely aware of online privacy issues and the ever-present threat of having a family reunion “Zoombombed.” The vulnerabilities of today’s video conferencing technology should raise some legitimate concerns for the California criminal justice system in the age of social distancing: remote access technology may be available, but is it reliable, secure and just how would it be implemented?

Nationwide, there are precedents for the use of remote access technology in court proceedings. Multiple states have had video conferencing pilot programs in place for a decade or more. Alaska, for example, has long authorized video arraignments in adult criminal cases. Since the early 2000s, the District of Columbia has permitted the use of video conferencing for prisoners who are parties to the proceedings but are incarcerated outside the jurisdiction. Several Florida courts use video conferencing for testimony and arraignments. According to journalist Bryce Covert, by 2002 “over half of states allowed video in some type of criminal proceeding.”

New Jersey leads the pack. Since 2001, the New Jersey Judiciary has maintained one of the largest video conferencing networks for court systems in the country, with Superior Court first appearances and central judicial processing (CJP) hearings regularly streaming live via the state’s innovative Virtual Courtroom network. (New Jersey continues to pioneer the use of video conferencing in criminal proceedings, including expert witness pretrial or trial testimony, child victim testimony and post conviction motion proceedings involving state prison or jail inmates.) New Jersey, however, is the exception that proves the rule. After almost two decades of experimentation, superior court use of video conferencing and remote access technology, especially for criminal trials, is still in its Beta phase.

Which brings us back to Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye’s orders and California’s emergency, COVID-19 inspired “technological imperative.” From a public health perspective, it makes perfect sense for California’s superior courts — and the Los Angeles County Superior Court specifically — to prioritize the rapid roll-out of video conferencing and remote access technology. But what about the many practical and Constitutional considerations that complicate our rush to tele-justice? How can client-attorney confidentiality be maintained? How will tele-justice impact not only what has been called “the persuasiveness of live witness testimony,” but more fundamentally, a defendant’s Sixth Amendment constitutional right to confront the witnesses against him? How will technologically-disadvantaged defendants participate in this high-tech future — what about those of us who do not have access to computers or the Internet? Finally, what about online security? What are the due process ramifications of a hacked or “bombed” proceeding?

The Los Angeles County Superior Courts are nevertheless forging ahead. On April 9, Presiding Judge Kevin C. Brazile issued a news release announcing that “all essential Dependency hearings” as well as Delinquency and Mental Health proceedings will be conducted via WebEx. (WebEx is part of the Cisco Digital Justice portfolio of video conferencing software; according to the corporate website, “The Cisco Digital Justice solution enhances the cycle of justice and lowers operating expenses for courts, corrections, and law enforcement. This approach allows court and correctional leaders, as well as law officers to perform their duties more efficiently—regardless of distance. It enhances agility, increases the speed of the justice process, and creates safer experiences for justice workers and inmates.” Needless to say, speed, efficiency and lower operating costs are bullet points in Cisco’s sales pitch — constitutional considerations go unmentioned.) Brazile then went on to extol the benefits of remote technology and its utilization by the Court. “Remote technology is a solution for social distancing in our courthouses and supports the Court’s General Orders to prioritize time-sensitive, essential services and hearings during this public health crisis. The Court’s extensive focus in recent years to leverage technology in all our operations laid the foundation for this quick transition.”

The latter sentence is jarring: just what “transition” is Brazile referring to? Brazile doubled-down in his General Order, issued on April 14, 2020. In that Order, arraignments and criminal proceedings such as preliminary hearings and sentencings are listed as “time-sensitive, essential functions,” but the Court is ostensibly still weeks — if not months — away from using remote technology to address them with any sort of regularity or efficiency.

It’s here that the Balkanization of the LA courts may have a deleterious effect on defendants’ due process rights. The infrastructure gap between the Airport Courthouse and the Foltz Criminal Justice Center is probably immaterial when arraignments are in-person. But if those arraignments are via video, differences in equipment quality can result in differences of equity. Not all video arraignments will necessarily be equal. Also, a critical component of criminal proceedings is the presence and support of a defendant’s family and friends, not to mention members of the general public. If only court personnel and “justice partners” may participate in virtual criminal proceedings, this network of supporters and citizen-witnesses is rendered irrelevant. In short, there are innumerable kinks still to be worked out before remote access technology is a dependable component of the LA criminal courts, not the least of which are due process concerns.

Social distancing has led to an astronomical increase in the use of video chatting tools, from Zoom and FaceTime to Google Hangouts and Cisco’s WebEx. These apps are just what is needed for “quarantini” parties and catch-ups with isolated friends and relatives. But the suitability of platforms like these to the unique purposes and sensitivities of our criminal justice system remains an open question. Rebooting our stalled justice system is a civic priority. But as with all matters technological, outstanding innovation is usually accompanied by significant risks, both known and unknown. We should all pay close attention to how our criminal courts navigate that challenge.