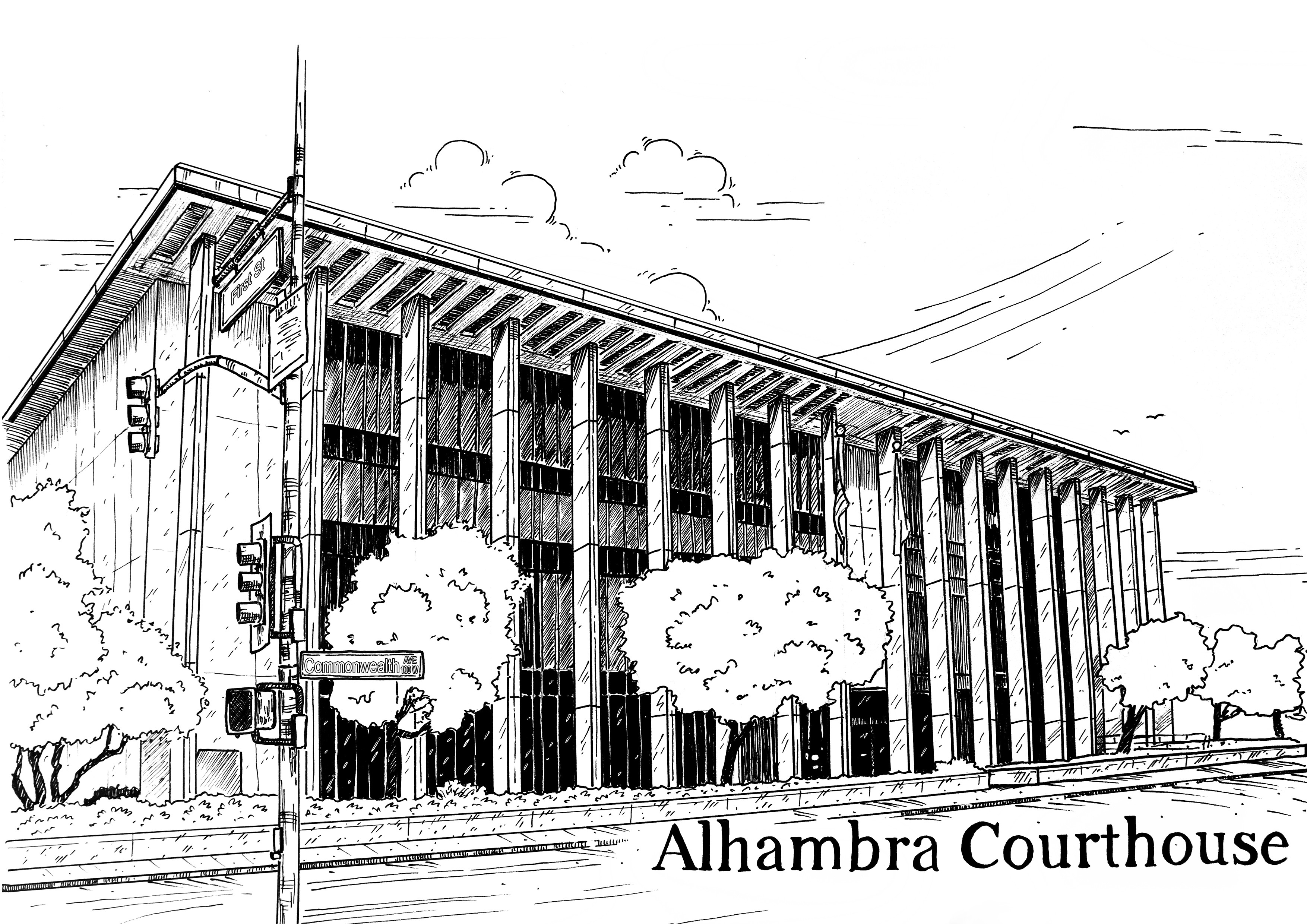

What does it mean, exactly, for something to be lost in translation? The answer, it seems, can be demonstrated in a densely packed courtroom in Alhambra.

Department 005 of the Alhambra Courthouse is unusually full, but that might just be because the entire left side of the gallery is blocked off by yellow caution tape, as if it were a crime scene. The remaining seating area is mostly occupied by people of Asian descent, though there are also a handful of Latinx folks and a Black man and woman sitting at the dead center of the room. The racial diversity is coupled with linguistic variety. Families and friends whisper to one another primarily in two languages — Chinese and Spanish — but also several other languages that I don’t recognize.

This room, and the courthouse around it, comprise an interesting microcosm of the region of Los Angeles County that it occupies. The city of Alhambra, located south of Pasadena and east of Los Angeles proper, can be seen as a kind of gateway into one of the nation’s most demographically interesting regions: the San Gabriel Valley. A longtime hub for ethnic and racial minorities — Latinx and Asian Americans in particular — entire swaths of the region are dominated by storefronts and strip malls with signage adorned with Asian-language scripts, usually Chinese. English names and translations sit off to the side, an afterthought. The SGV continues to evolve as Asians migrate to the region in droves. In the city of San Gabriel for instance, census data show that the overall population stayed about the same between 2000 and 2010, but the Asian population jumped from 49 percent to 61 percent. Every other racial group grew smaller.

And yet, in the midst of all this sits a courthouse still ruled by English-language proceedings. Interpreters abound in these halls. I count six on my day and a half of hearings in two different courtrooms: two Spanish and four Mandarin Chinese (two of whom also translate in Cantonese).

In Department 005, Judge Cathryn Brougham summons a Hispanic man sitting right in front of me. “Do you have an attorney?” she asks. He looks down to a younger woman, perhaps his daughter, sitting next to him. She translates for him in rapid-fire Spanish, ending with the English word, “lawyer.” He turns back to Brougham to respond, but before he can say anything, Brougham follows up: “Do you need a public defender?” “Yes,” the man replies in English, and though I worry he’s answering the wrong question, his daughter seems satisfied. I later realize that the man likely only needed his daughter to translate one word: “attorney.” Interestingly, she chose to do it with an English synonym.

Throughout that morning, a particular phenomenon recurs: Despite the bailiff’s preemptive warnings and admonitions, cell phones keep going off, and the culprits are all Asian. Now, being Taiwanese American myself, I hate to make assumptions about the language abilities of people who look like me. And yet, after the third or fourth sudden ringtone, I can’t fault Brougham when she makes what seems to be an unorthodox request of the three Chinese interpreters present in the room: She asks them to issue a final warning in Chinese. A female interpreter implores the audience in Mandarin to silence and put away their phones; the Cantonese interpreter presumably says something similar. The audience collectively nods in understanding. Still, the problem persists. At least two more phones go off, and one woman sitting next to me gets chided by the bailiff for playing Solitaire on her phone.

Amidst all this, the three Chinese interpreters resume their proper posts as Brougham commences the morning’s main event: a pre-trial hearing for Zhong Qi Chen, a man accused of murder. On a rather unassuming workday, Chen allegedly walked into his office at China Press, a Chinese-language newspaper based in Alhambra — he worked in sales for the paper — and shot his boss, founder and CEO Yining Xie, seven times in broad daylight. The majority of the day’s hearing involves the testimony of Mark Lin, a coworker who alleges Chen confessed to him minutes after the murder. Throughout Lin’s testimony, the interpreters rotate through a triangular formation: One stands next to Lin, translating questions to Mandarin and responses to English; one sits on the other side of the room by Chen, offering him a whispered play-by-play; and one sits in the jury area, taking a break.

It quickly becomes clear to me that Lin has some level of English-language proficiency. Most witnesses with interpreters I’ve seen tend to face or at least glance at them—a sign of dependency. But Lin looks directly at the person questioning him, be that the prosecutor, the defense attorney, or Brougham herself. He often answers prematurely, cutting off his interpreter before he can issue a full translation. A few times, he even answers “yes” or “no” in English.

Late in the hearing, crosstalk breaks out between the lawyers and Brougham. Lin appears to grow frustrated with his interpreter, who’s whispering a play-by-play into Lin’s ear. “I understand all of it,” Lin says firmly to his interpreter in Mandarin. The interpreter stands down momentarily; he does not translate this to English. It’s a stunning instance of clarity that sails over the heads of the bickering attorneys and judge, landing instead on the previously disengaged Chinese-speaking audience.

iPhones lower; ears perk up in recognition of Lin’s cleverness and subversiveness. But, seconds later, the action resumes, and the audience’s attention quietly drifts back to mobile games and social media feeds.