Massaging his wrists after having his handcuffs removed, Cedrick Deion Broussard stacks and organizes the slim pile of papers that he brought from holding with him: his SB 1437 petition to have the judge commute his murder conviction. Broussard does not have an attorney present, but he’s accompanied by a private investigator who listens quietly by his side.

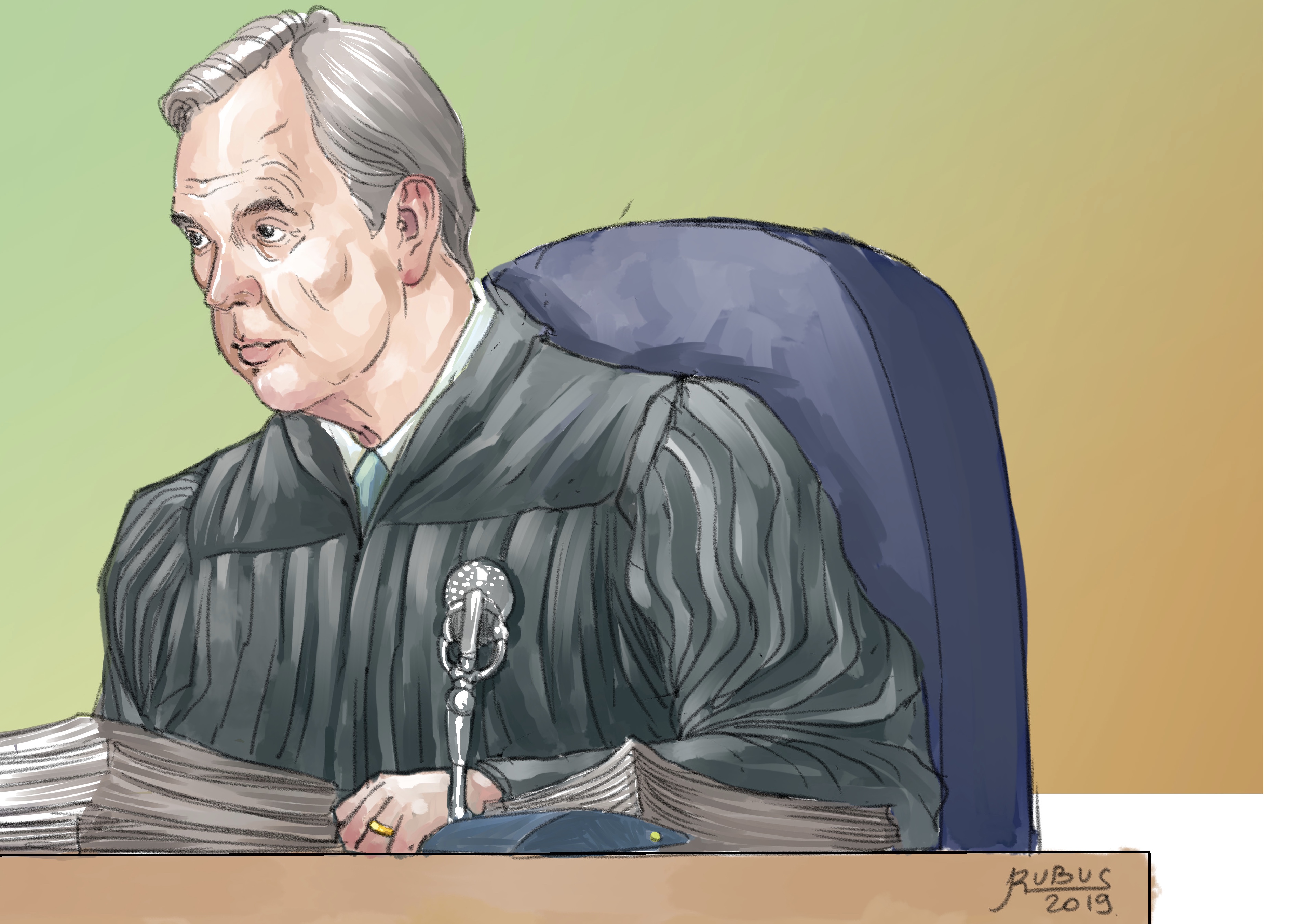

“I’m not going to re-try the case,” Judge Curtis B. Rappe repeatedly asserts, “even if one of the witnesses says, ‘Yes, I actually lied,’ I’m not going to re-try the case.” Broussard does not seem fazed by this response; he likely expected it. Throwing in a “Your Honor” as often as grammatically possible, Broussard nods and nods, rocking slowly in his seat, insisting that all he wants is to have his sentence reconsidered; he’s not asking to re-try the case.

Senate Bill 1437, signed into law in late 2018 by then-Governor Jerry Brown, greatly limits the legal requirements for an individual to be charged with felony murder. Now, to be convicted of felony murder, one must have killed, intended to kill, or acted with “reckless indifference to human life.” Under the previous statute, one could be convicted of murder for being a minor accomplice. With these changes comes the opportunity for individuals who, under the new guidelines, are no longer legally considered “murderers” to petition to have their sentences commuted or reconsidered.

Broussard’s case was originally heard 14 years ago, long before SB 1437 was on anyone’s mind. The jury convicted Broussard of second-degree murder, though they did not find that he had himself fired the gun that killed Tyzel Cards. But, since the murder was committed “for the benefit of… a criminal street gang,” and Broussard was present for the crime, he was nevertheless found guilty. Broussard’s argues that cases like his exemplify the now defunct felony murder rule in action, and that cases like these also paved the way for SB 1437.

In a video op-ed produced earlier this year by The New York Times, Adnan Khan explains the felony murder rule, and the story of how he, as an 18-year-old, was sentenced to 25 years to life for a murder that he did not commit. Khan was involved in a robbery with another man but did not know that his co-conspirator had a knife. Khan also didn’t know that his co-conspirator had a serious mental illness which may have led him to fatally stab the robbery victim, as Khan watched in confusion. The New York Times also reported on the case of Neko Wilson, a Fresno man who is facing the death penalty for allegedly helping to plan a robbery that resulted in the deaths of two people, despite the fact that Wilson was nowhere near the scene of the murders when they occurred.

These men were among the first individuals released after the passage of SB 1437. Broussard has been incarcerated for longer than either of these men and faces many barriers to securing a re-sentencing, among them the difficulties inherent in self-representation and the very specific and onerous requirements of SB 1437.

Despite these difficulties, however, Broussard holds his own in the courtroom. Stuttering occasionally and uttering the occasional “uh” or “um,” Broussard confidently knows the argument he is trying to make and refuses to let Rappe talk down his petition. He argues that his connection to the murder was tangential at best, and that he was charged alongside the “worst of the offenders,” despite having a limited role in the event. Broussard, it seems, could very well be the perfect candidate for the exonerative efforts promised by SB 1437 — if his interpretation of the law is accurate.

Deputy District Attorney Steven Mac asserts that, despite Broussard’s forceful arguments, he is unfortunately mistaken in his understanding of the law; Broussard crime involved the aiding and abetting of a murder, and those convicted of such charges cannot avail themselves of SB 1437. Rappe denies his petition.

If Broussard is angry or surprised by this dismissal, he does not show it. The bailiff walks over to him and returns the handcuffs to his wrists, this time placing them behind his back. Then, somewhat awkwardly, the bailiff picks up Broussard’s small stack of documents and places them in his manacled hands, making sure that the papers do not fall to the floor. Clutching his documents, Broussard exits the courtroom.

This will not be Broussard’s last appearance in Department 103. He and his private investigator will be returning for a hearing regarding a habeas corpus petition that he has also filed; Broussard will once again be representing himself in court. When asked his opinion about the proposed date of the subsequent hearing, Broussard responds, with only an inkling of irony, “Your Honor, I’m in prison. Whenever they wake me up in the morning and tell me to go, that’s when I go.” Rappe, intentionally obtuse, asks Broussard if this means “yes or no,” though Broussard’s acquiescence is crystal clear.

Still, Rappe is ultimately respectful and encouraging of Broussard. Faced with Broussard’s determination, Rappe eventually reins in his antagonistic bravado and begins to ask more questions and even offers some advice to the defendant. As jaded a jurist as he may be, the judge cannot ignore the fortitude of this man: arguing for his own freedom, navigating unfamiliar legal terrain, attempting to use new mechanisms that were crafted and instituted far away from the cell where he has waited for years.

Long after Broussard leaves the courtroom, Rappe asks the bailiff of the defendant’s location, hoping to hand him a set of freshly prepared court documents. It seems that the judge has noticed a string of errors and/or inconsistencies in the paperwork Broussard provided and wishes to advise the defendant on how to correct them. “Bring him back here on Monday,” the judge directs the bailiff, “we’ll work this out then.”